HOUSTON — With a week to go before Election Day, a showdown is emerging between state and local leaders here over how to protect the security of the vote without intimidating voters and election workers.

GOP push to monitor voting in Texas’s Harris County spurs outcry

The result could be a partisan showdown, in which two different sets of monitors face off on Election Day in this giant metro region. That’s not including the thousands of partisan poll watchers who are expected to fan out at voting locations across Texas.

GOP officials and conservative poll watchers say heightened scrutiny is necessary to prevent election fraud and mismanagement. Voting-rights advocates and local leaders, meanwhile, say the GOP is scaring voters and election workers alike — and undermining faith in the results for a county that Republicans are pushing hard to win control of on Nov. 8.

The conflict reflects how much mistrust has infused election season across the country, giving rise to fears of confrontation and even violence between groups with wildly divergent beliefs about how best to protect democratic rights. The dynamic is particularly heightened in the cities of politically contested states, where Democrats tend to control elections and where Republicans have mounted aggressive poll-watching campaigns.

The office of Texas Secretary of State John Scott (R) announced plans last month to send monitors to conduct “randomized checks” and observe handling and counting of ballots as a result of what he described as bungled election security efforts in 2020. The alleged problems, discovered during a state audit of Harris’s administration of the 2020 election, include improper security surrounding electronic equipment where vote tallies were stored, the letter said. Harris officials denied the accusations.

“We are writing to inform you that our ongoing audit of Harris County has revealed serious breaches of proper elections records management,” wrote Chad Ennis, who leads Scott’s Forensic Audit Division, in an Oct. 18 letter to the county’s new elections administrator, Clifford Tatum. “The urgency of this letter is to ensure that none of these process issues occur in the upcoming November 2022 general election.”

The letter noted that Republican Attorney General Ken Paxton would send a task force to Harris to respond to any legal issues flagged by inspectors, poll watchers or voters.

Last week, Paxton announced the formation of a statewide “2022 General Election Integrity Team.” The announcement encouraged Texans to submit “information about alleged violations of the Texas Election Code.” It wasn’t clear where else the team would deploy, and Paxton’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

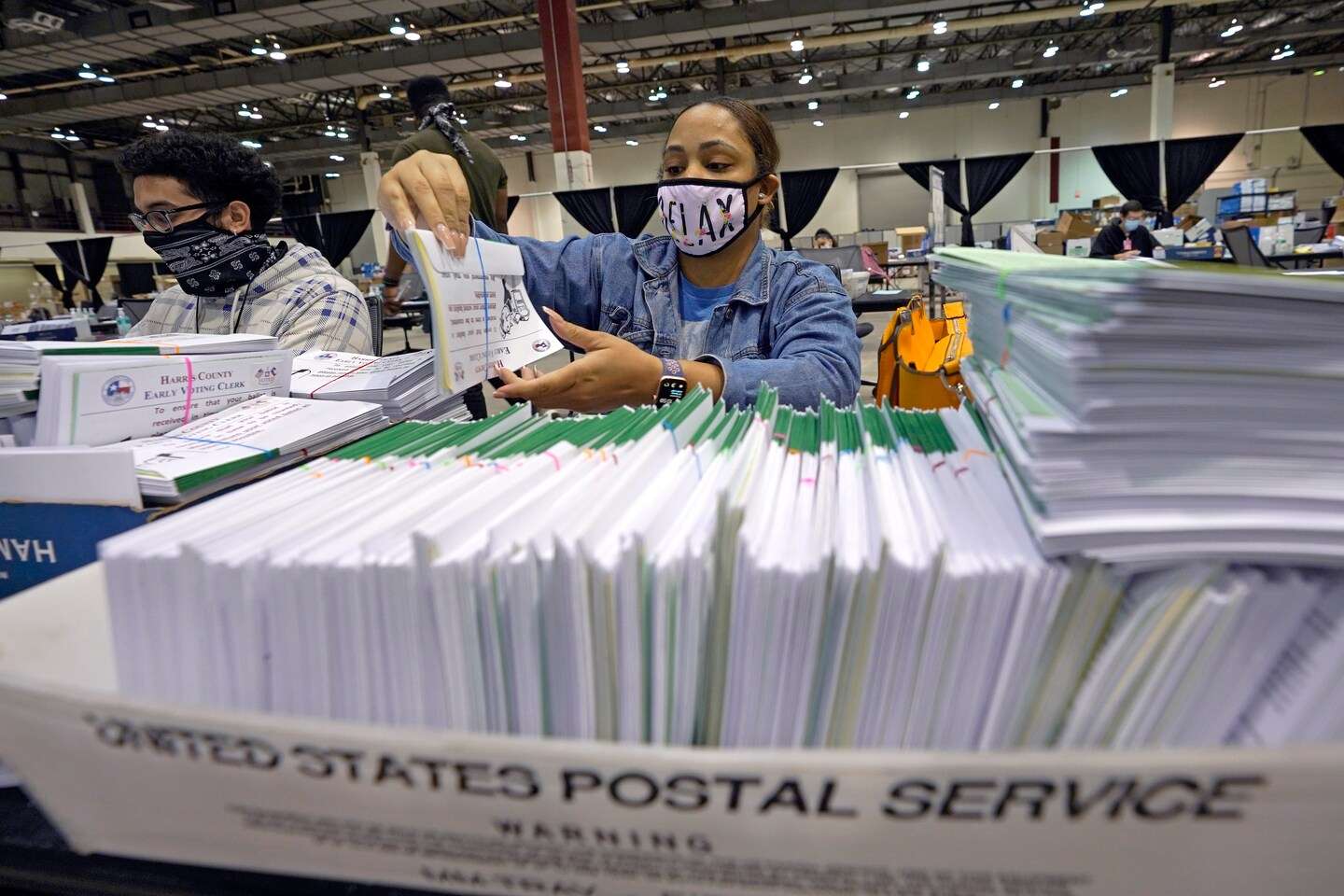

Harris County struggled during the March 1 primary, the first major vote under new state restrictions, when 10,000 mail ballots weren’t counted on Election Day and officials faced issues with new voting machines and a lack of poll workers. The election administrator later resigned.

The interventions from Scott and Paxton triggered an uproar from voting advocates, voters and Democratic leaders in Harris, who accused Republican officials of trying to intimidate election workers and voters in Houston.

Harris County Attorney Christian Menefee said in an interview that he, along with the county’s chief executive, Lina Hidalgo, and Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner — all Democrats — sent a request to the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division for federal election monitors to be deployed at polling and counting locations in Harris.

Menefee said he received an email from Kristen Clarke, assistant attorney general for civil rights, saying that she was looking into the request. He said he spoke by phone with DOJ staff, which typically publishes a list of places where it plans to deploy monitors about a week out from an election. The Department of Justice did not respond to a request for comment.

“Our biggest concern is we’re going to get to the counting process and there’s going to be folks from the attorney general’s office disrupting stuff in a bad-faith way,” Menefee said of Paxton’s office.

Menefee noted that both Scott and Paxton participated in Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election and backed the state audit of Harris, which Trump had requested. He called the state’s letter “vague and ominous,” intended as “a political tool to undermine our elections.”

He also rejected the allegation that the 2020 election was not secure. He acknowledged initial problems gathering votes from 14 machines. But those issues were documented and witnessed by election judges from both parties, he said, meaning the machines with stored vote tallies were always accounted for.

Hidalgo also assailed the state’s intervention. “The timing of this letter is — at best — suspicious,” she wrote on Twitter about the secretary of state’s announcement. “It was sent just days before the start of early voting, potentially in an attempt to sabotage county efforts by sowing doubt in the elections process, or equally as bad, by opening the door to possible inappropriate state interference in Harris County’s elections.”

Hidalgo is in a heated reelection battle against Republican Alexandria del Moral Mealer, who promises on her campaign website to “do everything I can to safeguard our ballots and ensure free and fair elections for Harris County voters. This starts by cleaning the voter rolls.” At a conservative forum earlier this year, Mealer declined to say that Trump had lost in 2020 — though she has said so more recently, during her general-election campaign.

Sam Taylor, a spokesman for the secretary of state, said much of the backlash over the deployment of monitors is overblown given that it happens every year — and is actually required by law when a certain number of voters request it, as happened this year. While 118 observers have been dispatched so far statewide this year, the number was 250 in 2020, he said. The monitors’ role is to observe election procedures and document issues such as security failures.

Harris is the country’s third-largest county by population, after Los Angeles and Chicago’s Cook County, and one of its most diverse, with a majority of its 4.7 million residents Latino, Black or Asian. Some residents have bridled at efforts to more aggressively scrutinize the work of local election officials.

“They don’t need people making an already difficult job more difficult,” said Clay Sands, 58, a real estate broker and self-described moderate Democrat who cast his ballot this week at a popular early-voting spot near downtown Houston.

The view was very different at a Harris County library branch in suburban Katy on Friday, where Johnny Wisniski, 65, a Republican and a public-works employee in a neighboring county, said he has little faith in the election process. He welcomed the presence of local and state monitors.

“I just think there’s going to be some cheating,” he said. “I think people are going to vote twice and dead people are going to vote. There’s going to be fraud.”

In addition to the government monitors, a surge of partisan poll watchers is expected at voting locations in Texas this year.

Taylor said more than 3,300 Texans have taken his office’s online training course for poll observers — a new requirement under a sweeping election law enacted in 2021. But there is no way to know how many of those will actually show up, or where, Taylor added.

Nadia Hakim, a spokesperson for the Harris County elections office, said the office received no reports of issues with poll observer misconduct, voter intimidation or major malfunctions of voting machines as of Friday, the midpoint of Texas’s two-week-long early-voting period. Several election administrators said they expect a burst of activity on Election Day.

Anthony Gutierrez, executive director of the nonpartisan voter education and advocacy group Common Cause Texas, said that while so far there have not been many complaints to his group’s hotline, he is concerned that poll observers could overstep in this year’s tense atmosphere. During a training last week, Gutierrez said volunteers reported seeing people without the required identification circulating at polling locations close to voters.

One Black voter complained to the hotline that when he showed up to vote at a polling location at a southwest Dallas community college, a White man outside told him he had to first surrender his cellphone and smartwatch, Gutierrez said. He said the voter complied, cast his ballot and recovered his items, only to discover the man who seized them “was not a worker at that poll site. They were just trying to be intimidating.”

A spokesman for the Dallas elections office confirmed multiple reports of poll observers trying inappropriately to confiscate phones and smartwatches from voters. Under state law, voters must put away their phones but can carry them into the polls. There is no requirement to remove smartwatches, he said.

One ingredient in the recipe for conflict, election administrators said, is the divergent understanding of what is allowed and what is not. Taylor said his office has received dozens of calls from observers describing poll-worker actions they assumed were illegal, but weren’t.

Harris County residents Wayne and Lisa Nellums said they worried about voters being intimidated by state poll monitoring, particularly fellow voters of color. But the couple, who are Black, said the added monitoring could also backfire on those they believe are seeking to drive away minority voters like them.

“What they don’t understand is that when they try to intimidate,” said Lisa Nellums, 61, “it just makes us want to vote more.”

Gardner reported from Washington.