Why the Supreme Court’s order in an Alabama voting case sends a troubling message

Yet in another crucial respect, the justices — and other federal courts — have been adding to the anxiety voters feel in this pandemic-shadowed election year. Specifically, the court decided 5 to 4 on Tuesday to block an Alabama federal judge’s order that would have made that state expand accommodations for voters in a July 14 runoff primary. The state is offering absentee ballots to all, but under very restrictive conditions requiring copy of a photo ID and two witnesses or a notary’s affidavit. On June 15, Judge Abdul K. Kallon struck down those onerous conditions for over-65 voters at high risk of contracting the coronavirus, and ordered Alabama to permit curbside voting in counties that wanted it. On June 25, a three-judge appeals court allowed Judge Kallon’s order to take effect pending a final decision on the merits — and then the Supreme Court stepped in to halt it, at Alabama’s request.

The justices offered no reasoning for their order, which is not unusual given the posture of the case. But it seems likely based on the same reasoning by which they halted a lower court’s six-day extension of Wisconsin’s absentee voting deadline in April: Judges should ordinarily not disrupt elections by changing important rules on the eve of the voting. That is a valid concern — yet also a highly subjective, and potentially manipulable, one. Exactly how close to Election Day is too close?

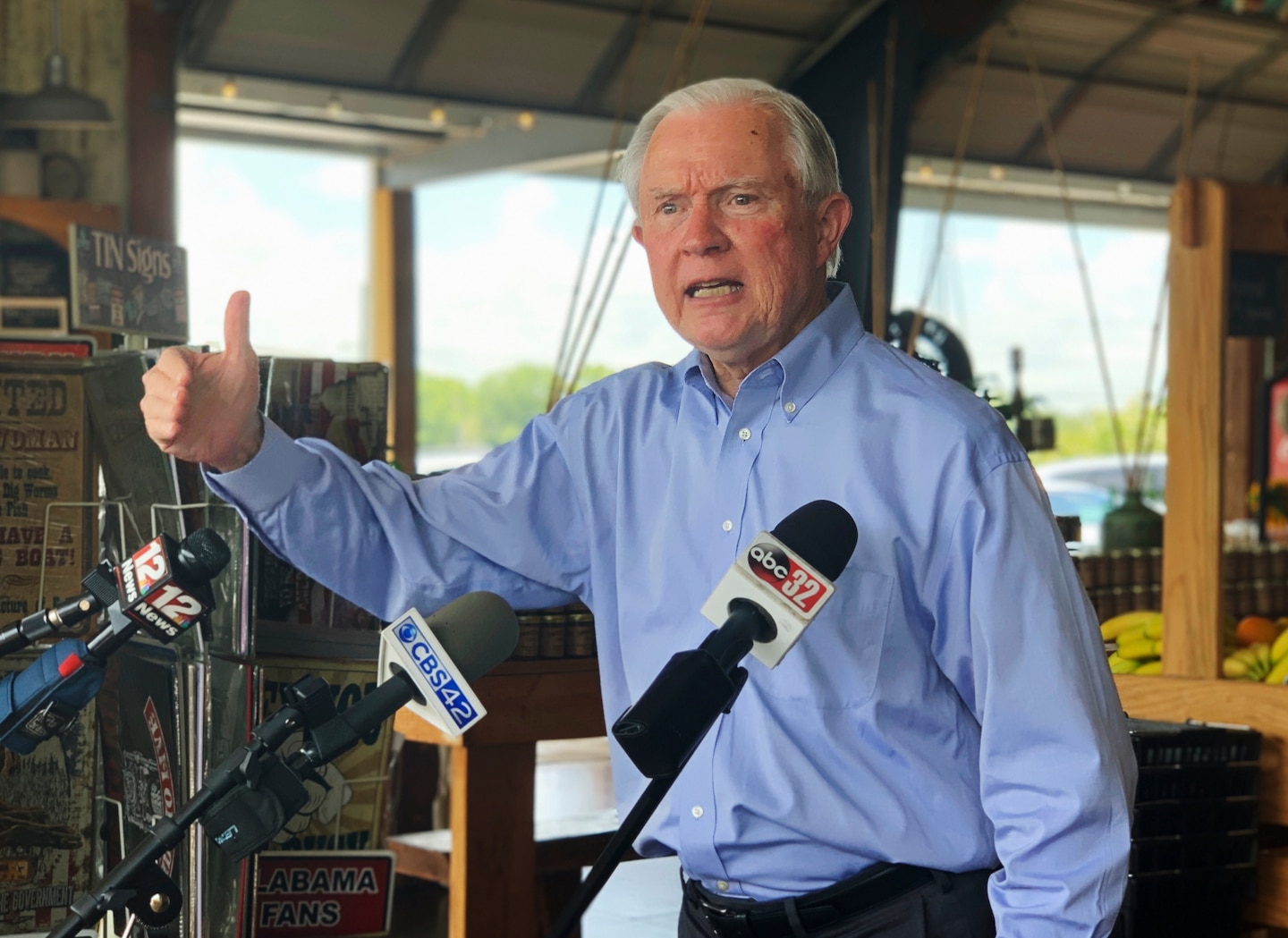

As a practical matter, the court’s Alabama ruling probably affects one major contested primary race July 14, the GOP Senate runoff. Still, together with the Wisconsin order, and a June decision leaving Texas’s tight restrictions on mail-in voting for under-65s at least temporarily in place, it sends a worrisome signal about the justices’ willingness to make sure that states maximize — rather than suppress — voting this fall.

The Alabama case reverts to the Atlanta-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, which sent a troubling message of its own in a separate case July 1. On that day, it halted a Florida judge’s May order forbidding Florida from requiring re-enfranchised ex-felons to pay fines and other costs before voting — contrary to the spirit of a 2018 referendum in which two-thirds of Floridians voted to restore ex-offenders’ voting rights. The 11th Circuit, newly staffed by a majority of Republican-appointed judges, thanks to President Trump and the GOP Senate, will hold a hearing Aug. 18 — the day of Florida’s primary. It may or may not reach a decision by Nov. 3.

In the meantime, no one knows for sure which Floridians, or how many, will be able to take part in that state’s presidential voting. This is the opposite of what stability, transparency — and basic fairness — require.

Read more: