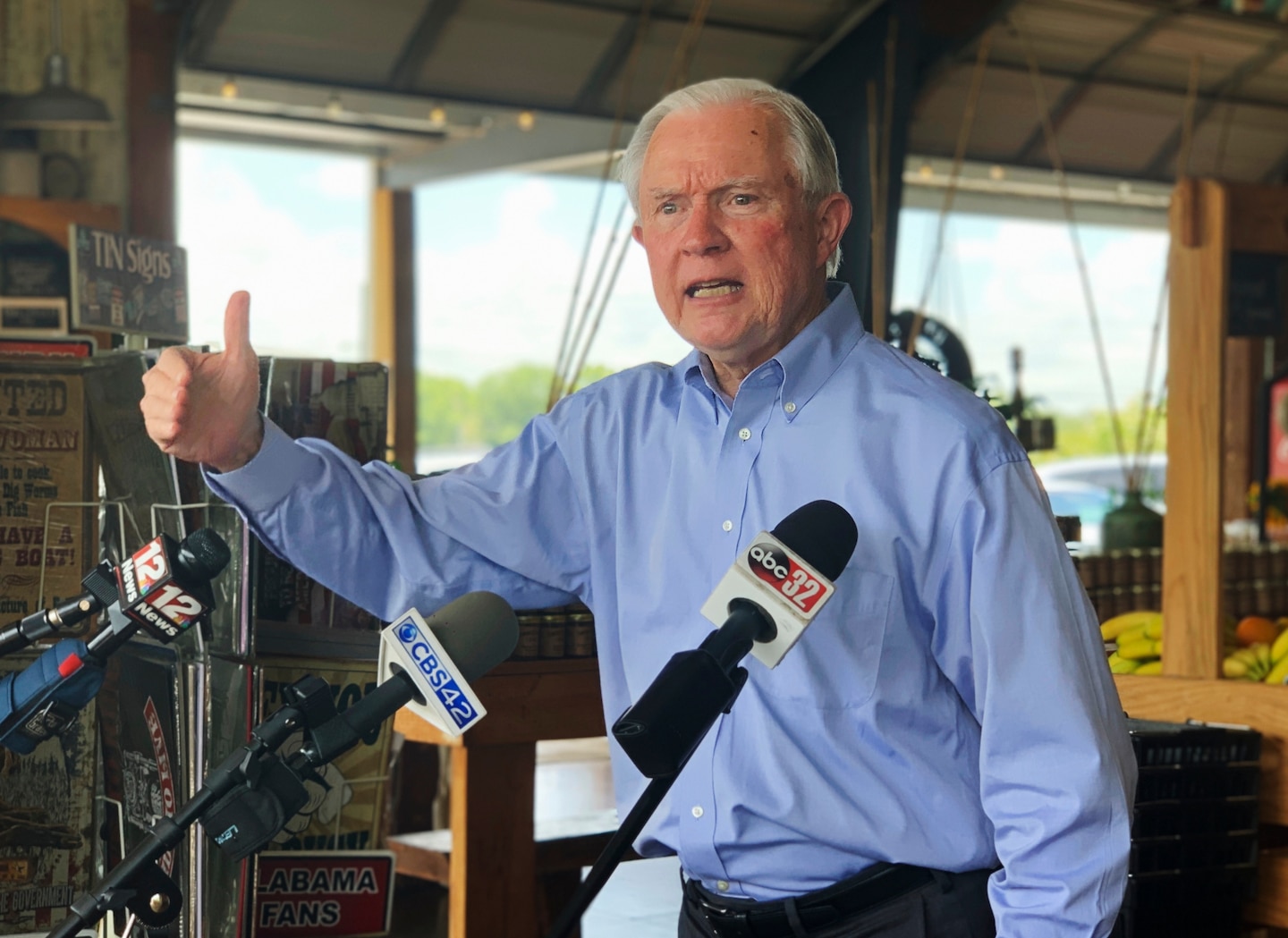

A onetime Alabama favorite son hopes to win back his Senate seat. Trump stands in the way.

It’s a curious message for Sessions, who is only running for his old Senate seat because he got fired from his previous job, attorney general, because he fell out of favor with President Trump. While the president’s popularity is dropping in most battleground states, Trump remains extremely popular among Alabama GOP voters who will choose their nominee Tuesday to take on Sen. Doug Jones (D) in November.

When Sessions bemoans Tuberville as “Washington’s choice,” he leaves out the fact that Washington is now Trump’s town. Indeed, the president has given a full-throated endorsement to Tuberville, tweeting Saturday that the candidate is “a winner who will never let you down. Jeff Sessions is a disaster who has let us all down. We don’t want him back in Washington!”

It was the culmination of roughly two years of Trump taunting Sessions, beginning when he was still running the Justice Department and continuing thereafter, because the former senator recused himself from control of the federal investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential campaign that was designed to help elect Trump.

Trump blames that one decision for the succession of events that led to Robert S. Mueller III getting appointed as special counsel and a nearly two-year inquiry.

Never mind that Trump ended up facing no charges. Never mind that House Democrats dismissed efforts to include portions of that probe in their impeachment case against the president. Never mind the fact that Sessions was Trump’s first major endorsement in early 2016 and provided the ideological muscle for his “America First” agenda that has reshaped the Republican Party.

This has left Sessions in a somewhat desperate place, trying to win back the Senate seat that he surrendered four years ago when the president offered him the chance to be attorney general.

“I’ve taken the road less travelled. Not sought fame or fortune. My honor and integrity are far more important than these juvenile insults,” Sessions, who repeatedly defends his recusal decision, tweeted in response to Trump on Saturday. “As you know, Alabama does not take orders from Washington.”

At the same time, Sessions’s campaign website described him as a “battle-tested general” ready to help the president in his fight for the “heart and soul of our nation.”

“It’s all about Trump. If you took a snapshot of the polls four to five years ago in Alabama, Jeff Sessions was the most popular politician in the state. He wasn’t that effective because he’s such an ideologue,” said Steve Flowers, a former state representative.

Flowers, like so many Alabama politicians, had a career that reflected the state’s evolution: He was first elected as a Democrat but switched to Republican in the 1990s as the two parties began their split into one focused on urban coastal states and the other on inland, Southern, mostly rural territory.

Sessions was ahead of that curve, rebelling against the old Democratic guard and joining the Young Republicans while in college in the late 1960s. It positioned him, beginning in 1981, to get a 12-year stint as U.S. attorney in the Reagan and Bush administrations, perfectly setting him up to run for the Senate in 1996 just as the GOP was fully on the march in Alabama and the Deep South.

“He was the most popular, being a right-wing Republican in a ruby-red state,” Flowers said of Sessions’s 20-year tenure as senator.

Now Sessions, 73, is a clear underdog to Tuberville, who has never run for office.

Everything about this race has been unusual, starting with the special election in late 2017 that Jones won in large part because Republicans nominated Roy Moore, the former state Supreme Court justice who The Washington Post reported pursued romantic interests with teenage girls while he was a lawyer in his 30s. Moore has acknowledged contact with the women but denied any sexual contact.

Republicans immediately eyed the November 2020 race as a potentially easy pickup, with the election synced up with Trump’s presidential reelection bid. Tuberville and others got into the race early, and then on Nov. 7, 2019, a year to the day after Trump fired him, Sessions made a late entry.

His team hoped that a 40-year history as the state’s most reliably conservative voice would slingshot him to victory, or, even if he narrowly missed the 50 percent threshold, he would then secure enough support for the originally scheduled March runoff.

By the time the ballots start getting counted Tuesday, Sessions will have spent more time in the runoff phase of the election than the initial primary.

The Trump taunts have been brutal and relentless — “not mentally qualified” — and did more than just signal the president’s displeasure with his attorney general and now during the campaign. Those voters who might still be inclined to support Sessions saw something in him that they never saw in the previous four decades: weakness.

“Sessions has just had to face what’s really a string of abuse and criticism from the president. And he just took it, like a good soldier. He took the verbal abuse. He took all the taunts. And cumulatively, it’s made him look weak. It’s made an impression on Republican primary voters that Sessions is weak and untrustworthy,” said Robert Blanton III, chairman of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Put that up against a famous college football coach, even if he did coach the rival of the state’s most famous institution, even if his teams beat Alabama six straight times, even if he did resign from Auburn after a terrible 2008 season; people here still remember the team’s 13-0 season in 2004, winning the SEC title and getting what many consider a raw deal by pollsters, finishing second in national rankings.

“The fact of being a football coach at a major program automatically gives him some degree of gravitas — someone they respect as a leader and authority figure,” Blanton said.

Sessions faces two other hurdles with voters that are hard to quantify but are definitely a factor: He’s both too familiar a face, and he’s someone who did not tend closely enough to his state.

The former attorney general’s name recognition is practically universal in Alabama, but among conservative voters, that can be a drawback. Trump captured the state’s imagination — finishing more than 20 percentage points ahead of his closest challenger in the 2016 primary — because he was an outsider who had never run for office and promised to shake up the system.

To many, Sessions represents that system. “He’s been in Washington a long time. He announces his campaign on the Tucker Carlson show, rather than in Mobile,” Flowers said.

Also, Sessions spent two decades in the Senate focused on broad national issues, such as immigration and trade, attracting aides such as Stephen Miller, who now serves in the West Wing as Trump’s top domestic policy adviser.

He was on the right side of those issues for the state’s conservative voters, but Sessions rarely focused on tending to the bread-and-butter needs of local governments and projects. Sen. Richard C. Shelby (R-Ala.), chairman of the Appropriations Committee, has handled that work and remains powerful enough a figure that, after he announced he would oppose Moore and write in another Republican, thousands of voters followed that lead, providing the margin of victory for Jones.

Shelby led a group of 11 Senate Republicans to endorse Sessions as soon as he entered the race, and those who support him privately defend his recusal as the right thing to do, given that career prosecutors recommended it because he had served as an official on the 2016 campaign.

By recusing himself, Sessions allowed a more independent investigation to go forward, and, when the final report ended without clarity on how much Trump officials knew about Russian interference, it could be more trusted by the public, according to one ally who spoke on the condition of anonymity to speak frankly. But in trying to protect the Justice Department’s integrity, he gave Trump something to beat Sessions up with and, ultimately, made his 2020 comeback attempt that much harder.

Shelby privately asked Trump to stay neutral. The president did just that during the first round of voting — but a week after the first ballot, he weighed in for the 65-year-old Tuberville.

That has made it easier for former supporters to drift away from Sessions, but local experts believe it is too soon to count him out, particularly given the uncertainty of turnout during a pandemic, even as requests for absentee ballots are up.

“There’s no way to know in this topsy-turvy world with coronavirus who’s going to show up on a hot-as-hell Tuesday in mid-July in Alabama,” Flowers said. “The older people who vote might have trepidation about getting out to vote. That’s why you can’t predict it.”

Still, just seeing Sessions so desperate has left many stunned.

“How many people are not able to win back their own seat? How many people lose the primary to regain their old seat? Yes, it would be a very sad ending to his political career,” Blanton said.

Velasco reported from Birmingham, Ala. Kane reported from Washington.