Hong Kong delays elections, citing virus, further eroding political freedoms

The makeup of the legislature in the interim, Lam said, will be decided by Beijing.

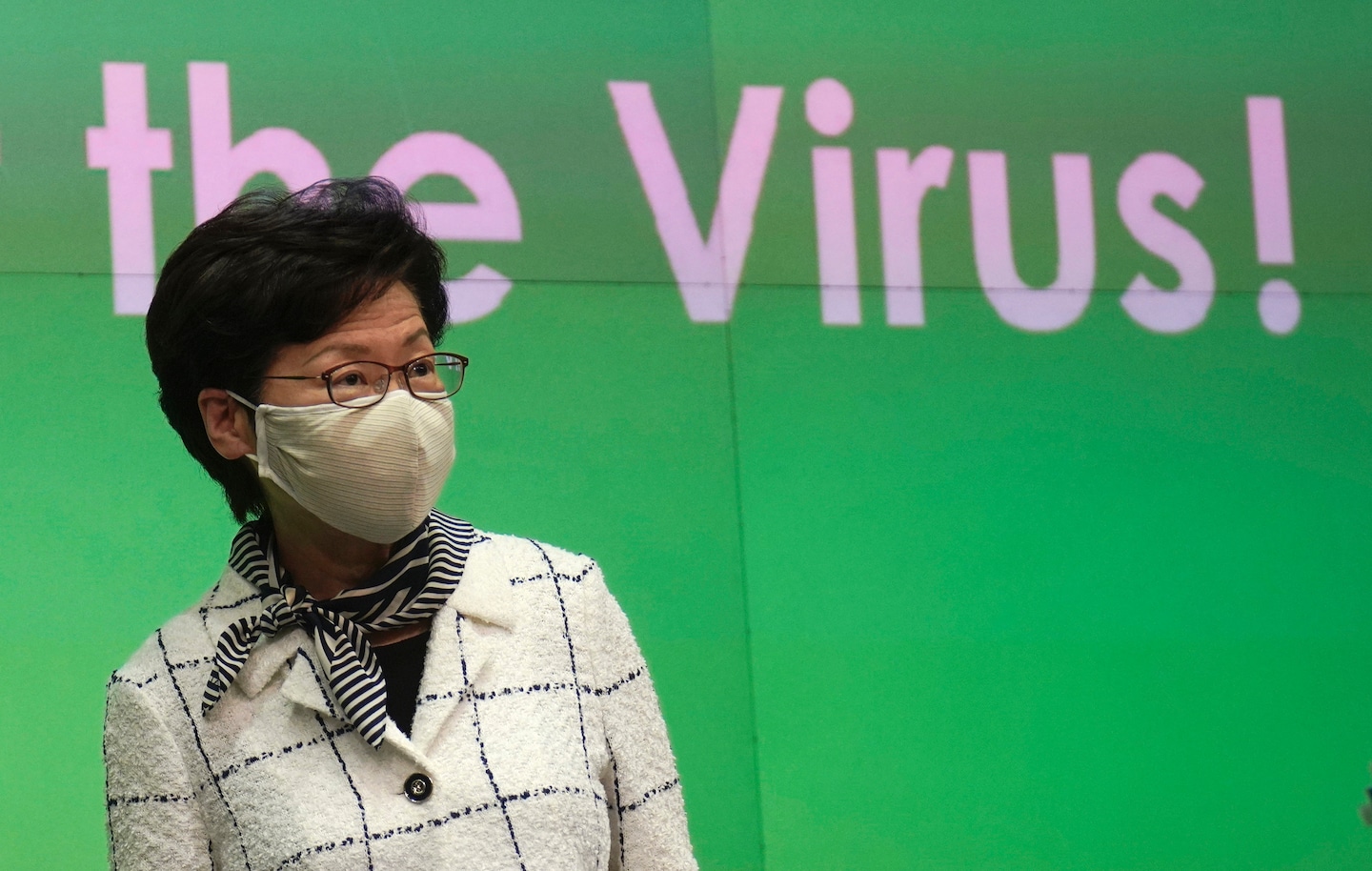

“We have made the decision to postpone the election for one year,” Lam said, after spending half an hour laying out her government’s response to the pandemic and the potential health risks of holding the vote. Because of the pandemic, “we would not be able to meet the requirements of an open and fair election,” she said.

In response to reporters’ questions, she added: “There is absolutely no political agenda.” The postponement, Lam said, was supported by Beijing since it is in the “public interest.”

Unconvinced, opposition politicians and observers said the moves are designed to stack the political system with those loyal to the Chinese Communist Party and snuff out even moderate political opposition in Hong Kong.

Beijing last month subverted Hong Kong’s usual political processes to pass a new national security law that has outlawed broadly worded crimes such as secession, foreign interference and terrorism. Several people, including teenagers, have been arrested under that law, which has rewritten the legal underpinnings of the financial center and has had a broad chilling effect on speech.

In that context, the Sept. 6 vote had loomed as a fierce contest likely to lead to a significant show of support for the pro-democracy opposition. Only half of the 70 seats in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council are directly elected, but given that the body has the power to enact and repeal laws, it is among the few avenues that residents have to express their political will.

“They have basically redefined their definition of their enemies, and from one red line, we now have a few. Those red lines have become very thick,” said Alvin Yeung, leader of the opposition Civic Party and one of the disqualified candidates. “This reflects that they — not us — are in fear, in fear of the people and of their voices.”

Pro-democracy candidates swept a majority of seats in local elections in November, a vote widely seen as an endorsement of their movement and a repudiation of the Beijing-allied elites.

Over the past year, pro-democracy legislators have tried to stall or vote down bills, including Lam’s proposal that would have allowed extraditions to mainland China and one that would criminalize mockery of the Chinese national anthem.

The vote will now be held on Sept. 5, 2021. Hong Kong does not have universal suffrage, and its chief executive is elected by a select committee from a pool of candidates approved by Beijing.

Lam herself acknowledged that the elections were the “biggest” in Hong Kong, with 4.4 million voters registered. Having so many people gathered, she said, poses a “great risk,” and registered voters who live in mainland China may not be able to travel into the city to cast their votes.

Countries such as Singapore and South Korea have held elections amid the covid-19 outbreak, which was severe in both places. In the 21 days since Singapore’s election, the city-state, which has a population density similar to Hong Kong’s, has not seen a jump in covid-19 cases, and daily community transmissions are in fact down to the single digits. Epidemiologists have noted that Hong Kong has begun to see gains in fighting this third wave of infections, and they predicted that daily cases, which have been a little over 100 in recent days, will likely drop in about four to six weeks.

Analysts have pointed out, too, that the Hong Kong government could have delayed the vote by a shorter period of several months and put in place a system such as postal or electronic voting. Other institutions of government, including courts that are currently prosecuting thousands of people arrested in pro-democracy protests last year, continue to be open as usual.

“Delaying it for a whole year is clearly overreach,” said Antony Dapiran, a lawyer and writer on Hong Kong politics. “It gives them time to suppress the opposition for another year.”

Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch, said the move follows a pattern in which the pandemic has been used as cover to suppress political dissidents in mainland China. Hong Kong, she said, has long been a standout in the administration of elections, which are conducted in an open, orderly way.

“Covid has presented a remarkably convenient excuse, but also a very shallow one,” Richardson said. “But what efforts have gone into considering alternatives to postponing the elections for a year?”

Several incumbent legislators who attempted to run again in this election, including Yeung and other members of his party, were among the dozen who were disqualified from running again on Thursday. Lam declined to say whether they will continue to serve as legislators for the next year.

The decision on what the legislature will look like for the coming year, she said, will be made instead by the highest political body in Beijing, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress.

“Everything is done in accordance with the law,” Lam added.

The disqualified candidates included prominent activists such as Joshua Wong, political newcomers including a former journalist and organizers of pro-democracy protests. Reasons cited included opposition to government policies and an opinion piece written by Wong in The Washington Post. The candidates, officials said, could not be trusted to uphold the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution.

“Clearly, this is the largest electoral fraud in Hong Kong’s history,” Wong said in a tweet.

The reasons cited by the government, Dapiran added, show that the national security law has in effect been much broader than expected, since it can now be used to disqualify anyone who does not explicitly support it.

“They are using the law to essentially find any pretense to outlaw political opposition wholesale, and disqualify as many as they can,” he said. “It now seems like any pretense of democracy has been taken away.”

Tiffany Liang contributed to this report.