A year and a half after the attack on the U.S. Capitol, Congress has passed precisely zero legislation to prevent it from happening again. But it could be close.

What is the Electoral Count Act, and why does Congress want to change it?

The House of Representatives passed its bill on Wednesday, with only 9 Republicans voting for it. Here’s what’s going on.

What is the Electoral Count Act?

The Constitution says states choose how to run their own elections. Once states determine which candidate won, they send those results to Congress.

Congress’s job is to simply count up each state’s electoral votes — with the vice president presiding over it all in a ceremonial capacity — and officially declare the winner of the presidential election. After that, all that’s left is to inaugurate the next president.

The Electoral Count Act is a 140-year-old law that governs what Congress and the vice president should do in the case of a dispute about which presidential candidate won in a state. (A legitimate dispute about who won the presidential election actually happened in 1876.)

But it’s an old and complicated law that experts say confuses, rather than guides, Congress in such turbulent times.

How did the Electoral Count Act come up on Jan. 6?

Trump and his allies twisted this law to pressure Vice President Mike Pence to try to throw out legitimate election results as Pence presided over Congress’s counting of states’ electoral votes.

Trump’s effort was aided by several Republican lawmakers who objected to certain states’ results, despite state officials and courts certifying them as legitimate.

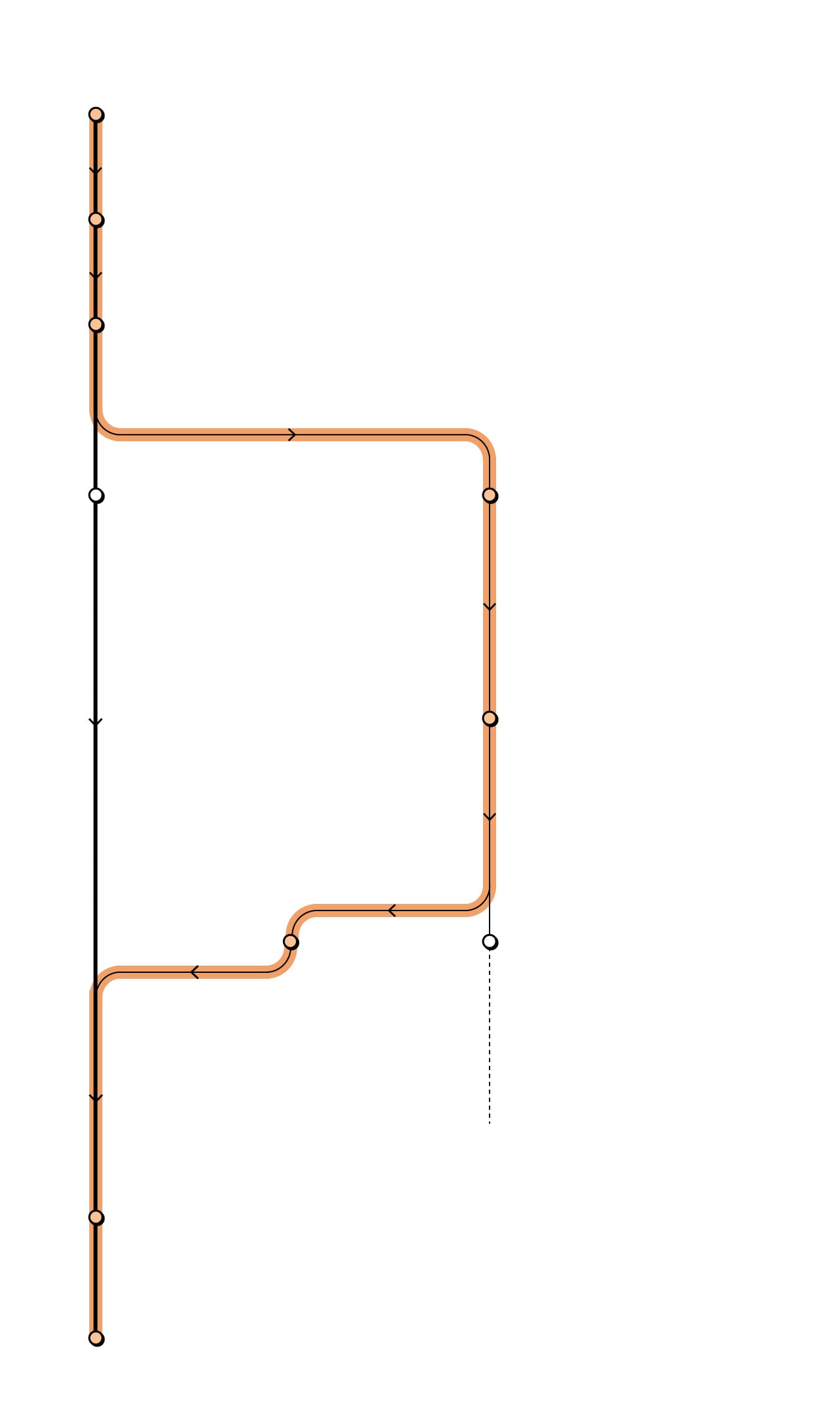

How the Electoral Count Act works

and how the process unfolded

in the 2020 election

Voters cast their ballots.

Election Day

The electoral college meets to certify states’ votes.

Later, States send electoral votes to Congress

for certification.

Congress convenes to certify each state’s

electoral votes. The vice president oversees

this as the president of the Senate.

No objection.

Two lawmakers, one from

each chamber, can object

to a state’s certification.

They don’t have to say why.

Jan. 6, around 12:30 p.m.:

Republicans objected to

Arizona’s results. They

would later object to

Pennsylvania’s as well.

Trump lost both states.

Congress votes on the

objection. The challenge

can be voted down by

a majority.

Jan. 6, around 1 p.m.:

Trump supporters violently

attacked the Capitol,

stopping the count for

hours.

Congress votes down

the challenge.

The vice president

does not have the

power to reject the

votes on their own.

Congress accepts the

challenge. The process

would involve the state’s

governor and the House

and Senate. Each step

opens up the possibility of

further legal challenges.

Congress certifies the winner

of the presidential election.

Jan. 7, 3 a.m.

The vice president announces

the winner of the election.

Jan. 7, around 3:30 a.m.

How the Electoral Count Act works

and how the process unfolded in the

2020 election

Voters cast their ballots.

Election Day

The electoral college meets to certify states’ votes.

Later, States send electoral votes to Congress

for certification.

Congress convenes to certify each state’s electoral votes.

The vice president oversees this as the president

of the Senate.

Two lawmakers, one from

each chamber, can object

to a state’s certification.

They don’t have to say why.

No objection.

Jan. 6, around 12:30 p.m.:

Republicans objected to

Arizona’s results. They

would later object to

Pennsylvania’s as well.

Trump lost both states.

Congress votes on the

objection. The challenge

can be voted down by

a majority.

Jan. 6, around 1 p.m.:

Trump supporters violently

attacked the Capitol,

stopping the count for

hours.

Congress votes

down the challenge.

The vice president

does not have the

power to reject the

votes on their own.

Congress accepts the

challenge. The process

would involve the state’s

governor and the House

and Senate. Each step

opens up the possibility of

further legal challenges.

Congress certifies the winner

of the presidential election.

Jan. 7, 3 a.m.

The vice president announces

the winner of the election.

Jan. 7, around 3:30 a.m.

How the Electoral Count Act works

and how the process unfolded in the 2020 election

How the Electoral Count Act works

and how the process unfolded in the

2020 election

Election

Day

Voters cast their ballots.

The electoral college meets to certify states’ votes.

Later, states send electoral votes to Congress for

certification.

Congress convenes to certify each state’s electoral votes

The vice president oversees this as the president

of the Senate.

Jan. 6.

Around 12:30 p.m.

One lawmaker from each chamber

is required to object to a state’s

certification. They don’t have to say why.

No objection.

Republicans objected to Arizona’s

results. They would later object to

Pennsylvania’s as well. Trump lost

both states.

Jan. 6.

Around 1 p.m.

Congress votes on the objection.

The challenge can be voted down by

a majority.

Trump supporters violently attacked

the Capitol, stopping the count for

hours.

Jan. 7.

3 a.m.

Congress accepts the challenge.

Next steps would involve the state’s

governor and the House and

Senate. Each step opens up the

possibility of further legal challenges.

Congress votes

down the challenge.

The vice president

does not have the

power to reject the

votes on their own.

Congress certifies the winner

of the presidential election.

Jan. 7.

Around

3:30 a.m.

The vice president announces

the winner of the election.

Pence ultimately determined the Constitution gave him no power to do such a thing and certified the results for Joe Biden, amid broken glass and a shaken nation.

Why are we talking about changing the law now?

It’s taken this long to find a compromise, particularly in the Senate, that has enough Republican support to pass. Making these changes means going directly against Trump’s will; he’s publicly bashed Republicans leading this effort.

But the Jan. 6 congressional committee’s investigation has underscored the urgency of preventing rogue actors from abusing the Electoral Count Act. If Trump’s plan had worked, retired federal judge J. Michael Luttig told the Jan. 6 congressional committee, it “would have been the first constitutional crisis since the founding of the Republic.”

The authors of a House bill to reform the law, Reps. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) and Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), warned in the Wall Street Journal this month that the GOP’s continued embrace of election lies “raises the prospect of another effort to steal a presidential election, perhaps with another attempt to corrupt Congress’s proceeding to tally electoral votes.”

What do lawmakers want to do?

They’re trying to figure that out. The House and Senate have competing bills, and they’ll have to come to agreement to get anything passed and to Biden’s desk. Plus, they’re running out of time before Republicans potentially take control of one or both chambers of Congress, and there is not a majority of support within the GOP for these changes.

One option that has the support of all lawmakers working on this: making it crystal clear that the vice president can’t override the will of voters — that their job is largely ministerial. (Republicans are fully aware that, in 2024, Vice President Harris will be presiding over certifying the victory.)

Lawmakers also want to raise the bar for how many members of Congress are required to challenge election results. Right now it’s two, one from each chamber.

The House bill would raise this threshold significantly, to one-third of lawmakers in each chamber. The Senate bill puts the threshold slightly lower, at one-fifth, report The Washington Post’s Marianna Sotomayor and Leigh Ann Caldwell. (After the Jan. 6 attack, some Republicans reversed their initial decision to question the results. But 139 House Republicans still voted not to certify certain states’ election results. Eight senators joined them.)

Both bills also try to clarify part of the law — basically, an unclear rule about the timing of a state’s election — that could allow bad actors to argue a state’s electors aren’t legitimate.

Lawmakers also want to, in some ways, make it easier for a presidential candidate to challenge election results — but only up to a point. They may create a special court for them to adjudicate their claims, with a pipeline directly to the Supreme Court. The hope is that this would settle any disputes quickly.

The proposals also try to address what would happen if a governor refuses to certify results. (The presidential candidate can sue them.)

There are still major details the House and Senate need to work out, and the debate could take the rest of the year to finish. But Congress is closer than ever to doing something to prevent another election dispute like 2020’s — and its ensuing political violence.

This has been updated with the latest news.